The ozone layer is on the way to full recovery.

Madrid, Sep 15 (EFE).

After decades of deterioration, the ozone layer, that thin strip of the atmosphere about 25 kilometers high that protects life on Earth from the sun’s rays, is in the “recovery process,” although it will still take half a century to return to pre-1980 levels, explained Alberto Redondas, a scientist at the Aemet atmospheric observatory in Izaña (Tenerife), in the Spanish archipelago of the Canary Islands.

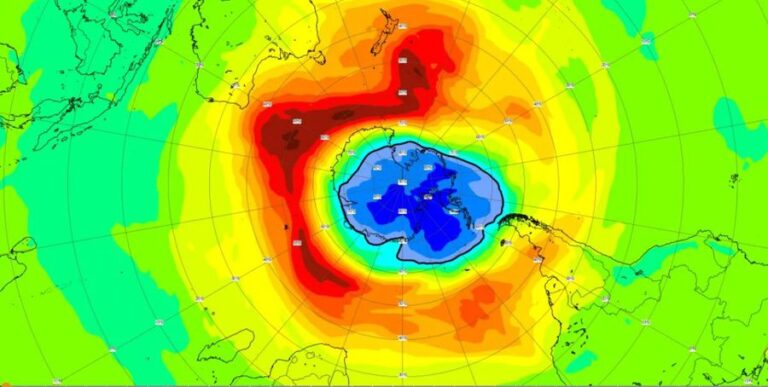

Compliance with international agreements has been crucial to avoiding setbacks in a problem that is concentrated in the South Pole, over Antarctica, and to a lesser extent in the North Pole and that decades ago seemed “insurmountable,” explained Redondas in an interview with EFE, on the occasion of World Ozone Day, whose theme this year is “From Science to Global Action.”

It is necessary to “continue vigilance” because threats do not cease: Phenomena such as large volcanic eruptions, massive forest fires, or even the entry of space debris into the atmosphere can damage this invisible shield, which makes life possible, the expert emphasizes.

Furthermore, this recovery varies from year to year. For example, in 2023 the hole over Antarctica was one of the largest on record, while in 2024 it was one of the smallest, indicating a positive trend toward ozone layer recovery. In 2025, the hole is close to average.

Almost 40 years ago, nations adopted the Montreal Protocol to eliminate chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), gases that began to be used in the 1930s in refrigerators and aerosols such as medicines or fire-extinguishing systems. When they react in the stratosphere with the three oxygen atoms that make up the ozone molecule, they destroy it, creating the so-called “ozone hole.”

For the scientist, international ozone treaties are a milestone in environmental protection agreements and exemplify the concept of moving from science to global action.

Question: What is the current state of the ozone layer?

Answer: The signs of recovery are clear, but the ozone layer is not expected to return to previous levels for another 50 years. This is because ozone-depleting substances remain in the atmosphere for decades. Furthermore, illegal emissions are still being detected—as occurred in China between 2013 and 2018—and unregulated compounds also affect the ozone layer.

Q: Why is the ozone layer so important for life on Earth?

A: Because, literally, we’re alive thanks to it. Located about 25 kilometers high, this layer protects us from the sun’s ultraviolet radiation, which can damage DNA. Without this barrier, life wouldn’t have been able to leave the sea and colonize land. It’s what has allowed ecosystems to develop as we know them.

Q: What consequences would its weakening have for human health and ecosystems?

A: They would be very serious. In humans, the incidence of skin cancer and cataracts would increase, and the immune system would weaken. In ecosystems, the impact would begin with plankton and phytoplankton—the base of the marine food chain—and extend to all organisms. Amphibians and certain plants are especially sensitive to ultraviolet radiation.

That’s why international action was crucial: “Thanks to the Vienna Convention and the Montreal Protocol, a scenario in which ultraviolet radiation could have increased by between 25% and 100% was avoided.

Q. Does climate change influence the ozone layer?

A. The relationship between the ozone layer and climate change is bidirectional. On the one hand, the ozone hole has altered rainfall patterns, especially in the southern hemisphere: in regions such as Australia, Patagonia, and areas near Antarctica. On the other hand, climate change also impacts ozone. The increase in CO₂ in the atmosphere cools the stratosphere, which somewhat slows ozone destruction.

However, this same process modifies the atmospheric circulation that transports ozone from the tropics to higher latitudes, leaving tropical regions more vulnerable. A decrease in the amount of ozone is, in fact, expected in these areas, which could have significant consequences for their ecosystems and populations.

Q. What can citizens do to contribute to its protection?

A. Most of the work was done in the 1980s with the ban on ozone-depleting substances. Now, the most important thing is to curb climate change, because it has become the main indirect threat to this layer.

Q. Is there sufficient social awareness on this issue?

A. In the 1990s, the ozone hole was on the front pages and in newscasts; not anymore. However, there has been a great deal of outreach work on the effects of ultraviolet radiation. There are recurring campaigns, especially on skin cancer prevention, that help keep social awareness alive, although perhaps not as intensely as it was then.